Cultural standards

What is culture?

We often talk about ‘ancient cultures’, ‘western culture’, the ‘cultural gap’, a ‘man of culture’…

What do you think the word ‘culture’ means? It may help if you think of your own cultural environment – which elements would you describe as typical?

Maybe you think of architecture, art, music, language, food, dress, literature, habits, values, ways of thinking, rituals and much more. All of these are elements of a certain culture. Sometimes we may talk of national cultures, of local cultures or even the culture of an organisation or social group.

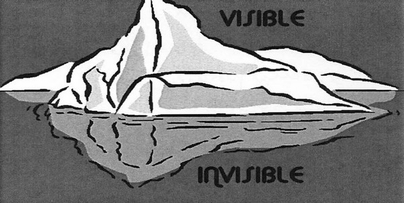

The Iceberg model

A useful way to visualize culture is by using the Iceberg model.

The iceberg has a visible tip. This is the part of a culture that we can see in the physical sense. "Visible" elements include things such as music, dress, architecture, language, food, gestures, religious rituals, art and more.

The part of the iceberg we can’t see – the largest part - includes areas such as religious beliefs, the rules governing relationships, family, motivation, tolerance of change, attitudes to rules and regulations, communication styles, comfort with risk, the difference between public and private spheres, gender differences and more.

It is these invisible elements that are the underlying drivers of those areas of culture which are visible to us. None of the visible elements can ever make real sense without also understanding the drivers behind them.

We all have our own ‘Iceberg’

Perhaps we can reach an even better understanding of the concept of culture if we start by asking ourselves about what we think our own cultural “Iceberg” looks like.

Ask yourself the following questions:

- What does it mean for you when somebody you have an appointment with is not on time – do you think it is disrespectful or not?

- Who would you rather ask if you were desperately in need of some money – your family or the bank?

- If somebody tells you in a straightforward manner that you are mistaken – do you find it helpful or do you feel affronted?

- Do you think that small talk at the beginning of a meeting is important in order to create a good atmosphere or a waste of time?

You will probably notice that it is difficult to answer these questions. It is impossible to be sure what the right answer is in each case. There is no straightforward ‘True’ or ‘False’. What seems right to you will not necessarily be right for somebody else.

How we choose to answer the questions above depend on our own values, attitudes, communication habits, mind sets – there are no ‘right’ answers. These are all elements of our culture which we have internalized since birth. They are passed on from generation to generation and help us find our way through the world. Seen in this way culture can be described as an orientation system (Alexander Thomas). [link to read more]

Culture as an orientation system

Culture provides us with an orientation system typical of a specific nation, a specific society, an organisation or a group. The orientation system consists of specific symbols (language, gestures, facial expressions, dress-code, greeting conventions etc.). It is passed on from generation to generation, creating a sense of belonging. Culture defines and influences our perception, our thinking, our values and actions.

We all have internalized our group’s culture and most of the time we are not aware of its function in guiding us through the things we experience in our lives. Our culture-specific orientation system helps us to understand what we see and what we perceive. It provides us with behavioural motivators and opportunities but also sets the conditions and limits of our behaviour (Alexander Thomas).

Successful enculturation, - integration into a new culture - requires a process of understanding and, finally, an acceptance of the world in the same way as those who originate from the culture perceive and accept the world.

There are countless other definitions of culture

Culture, understood as an orientation system, is only one of many definitions of culture. Here are some others:

Culture is ...

- the part of the environment which is made by humans (Harry Triandis)

- a collective programming of the mind (Geert Hofstede)

- the way in which a group of people solve problems (Fons Trompenaars)

Cross-cultural conflict arises when the hidden parts of the ”Iceberg” collide

Have you ever noticed how some cultures unconsciously define respect in different ways? For example some define respect by punctuality and keeping rules, others define respect through harmony and politeness?

Cross-cultural conflicts often arise not because what of what we actually see, but because of something is triggered which deeply disturbs us at an emotional, subconscious level. Do you remember the “Iceberg” model? Cross cultural conflict arises, when two (or more) hidden parts of the iceberg collide.

Each person has their own individual cultural imprint with its own set of values, norm, beliefs and attitudes. These elements help us to understand the world we live in and guide our perception of the world around us. So, depending on our own culture, we will interpret other people’s visible behaviour differently: it may seem more/less strange, acceptable or unacceptable to us. We see the world through our own cultural lens.

How to avoid cross-cultural conflict

To avoid cross-cultural conflict we have to learn to see what the world looks like without our own cultural lens. Here are some helpful steps to follow:

- Actively observe the situation – when you are disturbed or confused by an incident, take a close look at exactly what has happened or is happening.

- Describe the situation - make a mental description of what, specifically, it is that disturbs you in the situation.

- Allow multiple interpretations - your cultural background and your cultural orientation system are likely to lend the situation a particular meaning. Remember that in another context and in another culture, what you experience may have a totally different meaning.

- Suspend judgement - spend time and effort finding out what the disturbing behaviour really means in that culture. Refer to neutral third parties who are from, or acquainted with, that culture.

- Listen actively - make a conscious effort to listen to what you hear. Be aware that your cultural “map” will automatically lead you to filter and interpret what you hear.

- Understand perspectives - the more time you can spend understanding the values, beliefs and attitudes of people of other cultures, the higher your chances of long-term co-operation with minimal conflict.

- Establish rapport - turn the focus to what you have in common and what you can learn from each other. Remember that all cultures are equally good.

- Save face - make it possible for all parties to feel appreciated and respected. Loss of face is a major cause of intercultural conflict. Be aware of your own need not to lose face too.

- Develop WIN-WIN solutions - when the ground has been laid for mutual co-operation and understanding, and people are willing to work creatively together on solutions which are good for all parties, a conflict-free future is in sight.

How to assess culture: The Dimensions of Culture

The concept of cultural dimensions is a tool that has been developed to help us observe, understand and compare cultures. Cultural dimensions provide a basis for reflection concerning behaviour which may seem strange to us.

The dimensions described here are taken from the works of the most well-known developers of cultural dimensions, Geert Hofstede, Fons Trompenaars and Edward T. Hall.

Of course there is the risk of stereotyping when one tries to attribute what are ‘typical’ behaviours. But one has to keep in mind that cultural dimensions are based on what can be observed and what is normal for most members of a certain culture. It is important to remember to approach another culture not by looking at it through one’s own cultural lens but by observing it neutrally and by postponing judgments.

The following dimensions of cultural difference are described below:

- Power distance

- Individualism/Collectivism

- Uncertainty avoidance

- Masculinity/Femininity

- Universalism/Particularism

- High/Low context

- the concept of ‘Face’.

a) Power Distance

Are you accustomed to hierarchical structures in organisations? Or do you expect to be able to meet your boss in your free time?

This dimension concerns the extent to which an imbalance of power is accepted by a culture. A culture with highly hierarchical structures has a high power distance. Cultures with low power distance have very flat hierarchies.

| LOW Power Distance Index | HIGH Power Distance Index |

| Decentralised decision structures | Centralised decision structures |

| Flat organisational pyramids | Tall organisational pyramids |

| Small proportion of supervisors | Large proportion of supervisors |

| Hierarchy is established for convenience | Hierarchy reflects the existential inequality |

| Consultative leadership | Authority-based leadership |

| Subordinate-superior relations are pragmatic | Subordinate-superior relations are polarised |

| Institutionalised grievance channels | No defence against abuse of superior |

| Privileges and status symbols are frowned upon | Privileges and status symbols are popular and expected |

b) Individualism/Collectivism

Do you see yourself as engaged in a common cause or as an individual standing alone?

Members of collectivist cultures regard themselves as members of a group; they try to align their goals with those of the group and feel an obligation to the common good.

Members of individualist cultures regard themselves primarily as autonomous individuals and aim to reach their personal goals independently from the overall interests of their social group.

| Collectivism | Individualism |

| People act in the interest of the group they belong to | People act according to their personal interest |

| Group/family as reference point | Self-determination |

| Tightly-knit social framework | Loosely-knit social framework |

| Group responsibility for tasks | Individual responsibility for tasks |

c) Uncertainty avoidance

Do you feel comfortable in risky or ambiguous situations?

For people from cultures with high uncertainty avoidance, unclear, unregulated situations create a feeling of disorientation which can even lead to aggression. In such cultures, rules which regulate private and public life tend to attract a high level of respect.

For the members of cultures with low uncertainty avoidance, rules to regulate private and public life may be less strictly followed. Chaos and unclear situations are reacted to with relative ease.

| Low Uncertainty Avoidance | High Uncertainty Avoidance UAI |

| Precision and punctuality have to be learned and managed | Precision and punctuality come naturally |

| Power of superiors depends on position | Power of superiors depends on control of uncertainties and relationships |

| Innovators feel independent of rules | Innovators feel constrained by rules |

| Innovation is welcome but not necessarily applied consistently | Innovation is resisted but, if accepted, taken seriously |

| Scepticism towards technological solutions | Strong appeal of technological solutions |

d) Masculinity/Femininity (Geert Hofstede)

Do you have many female senior physicians in your country? Do nurses tend to be mostly women?

This dimension expresses the extent to which a culture defines and differentiates between gender roles. In masculine cultures, the social roles of each gender are clearly separated and the male role is characterized by an emphasis on high performance, assertiveness, dominance and material gain. The feminine role is characterized by caring, modesty, subordination, and warm-heartedness. In feminine cultures, roles are not defined by specific characteristics and almost all roles in society can be filled by women as well as by men.

| Femininity | Masculinity |

| Work in order to live | Live in order to work |

| No visible traditional assignment of roles | Visible traditional assignment of roles |

| Meaning of work = relations and working conditions | Meaning of work = security, good pay |

| Stress on equality, solidarity, quality of work life | Stress on equity, competition, performance |

| Successful managers: use intuition, deal with feelings, consensus | Successful managers: firm, aggressive, decisive |

| More women in high positions | Fewer women in high positions |

| Small wage gap between genders | Large wage gap between genders |

| Career ambition optional for both men and women | Career ambition compulsory for men, optional for women |

e) Universalism/Particularism (Fons Trompenaars)

Would you help a patient or a colleague in need even if this means disobeying a rule?

This dimension describes how far in a culture rules are universally accepted and obeyed under all circumstances. Universalist cultures are convinced that this is possible, particularist ones focus much more strongly on specific circumstances and reject strict adherence to rules.

| Universalism | Particularism |

| Golden rules (do not lie, do not steal) | Focus on present circumstances, exceptions are possible (I would not steal from a friend) |

| Place greater importance on agreements | Place greater importance on relationships (I must help a friend, no matter what the rules say!) |

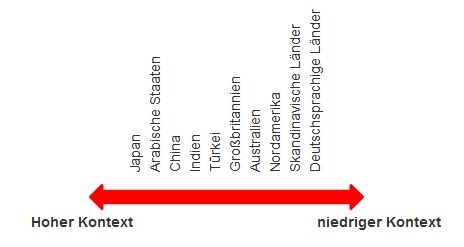

f) High/Low context (Hall)

How direct are you in telling patients about the severity of their illness? How do you choose your words when telling a colleague that their diagnosis is incorrect?

Low context cultures are accustomed to stating explicitly what they mean. The focus will be on the literal meaning of the message. There is no reading between the lines and both non-verbal communication and body language have little importance.

High context cultures communicate with indirect messages. There is much reading between the lines and non-verbal communication is important in decoding meanings correctly.

| High context culture | Low context culture |

| A strong focus on non-verbal communication and contextualised meanings | Little focus on non-verbal communication; overt, explicit messages |

| Reserved, internalised reactions | More focus on verbal communication than on body language |

| Relationship more important than task | Task more important than relationship |

Picture: High context Low context

g) The concept of ‘Face‘

The concept of ‘Face‘, although not defined as a cultural dimension, is nevertheless a widespread behavioral phenomenon.

Face is a term which is used particularly in Asian cultures, especially China. The notion of ‘face’ also exists in Western societies where it may be called ‘honour’, ‘prestige’, or ‘standing’.

In both Asian and Western cultures, ‘saving face’ can be particularly important and transgression of social norms and behaviour can lead to loss of face. In Asian cultures particularly, people tend to strive not only to avoid losing their own face but not to cause others to lose theirs. They also cooperate to help others to gain face.

References

- Matthias Bastigkeit, Können Sie mich verstehen? Sicher kommunizieren im Rettungsdienst. Wien 2005.

- Silke A. Becker, Eva Wunderer, Jürgen Schulz-Gambard, Muslimische Patienten. Ein Leitfaden zur interkulturellen Verständigung im Krankenhaus und Praxis. 3. Ed. Wien/New York 2006.

- Geert Hofstede, Culture and Organization – Software of the Mind, London 1991.

- Ilhan Ilkilic, Begegnung mit muslimischen Patienten. Eine Handreichung für die Gesundheitsberufe. Reihe Zentrum für Medizinische Ethik. Medizinethische Materailien, Heft 160 Burkhard May, Hans Martin Sass, Michael Zenz (eds.), 6. Ed., Bochum 2005.

- Malika Laabdallaoui, Ibrahim Rüschoff, Umgang mit muslimischen Patienten, Bonn 2010.

- Michael Peintinger (ed.), Interkulturell kompetent. Ein Leitfaden für Ärztinnen und Ärzte, Wien 2011.

- Alexander Thomas, „Kultur und Kulturstandards“, in: Alexanter Thomas/Eva-Ulrike Kinast/Sylvia Schroll-Machl (eds.), Handbuch Interkulturelle Kommunikation und Kooperation, vol. 1, 2. Ed., 2005.

- Harry C. Triandis, „Intercultural Education and Training“, in: Peter Funke (ed.), Understanding the US – Across Culture Prospective, Tübingen 1989.

- Fons Trompenaars, Riding the waves of culture, 2. Ed., London 2010.

- Charlotte Uzarewicz/Gudrum Piechotta (eds.), Trankulturelle Pflege, Reihe Sonderband zu Curare, 10, Berlin 1997.