LITHUANIA | Medical | Cultural standards

Content

A. Definition of culture

B. The Iceberg Model

C. Avoiding intercultural conflicts

D. Cultural standards - in general and in the medical context

- power distance

- Individualism/Collectivism

- Uncertainty avoidance

- Masculinity/Femininity

- Universalism/Particularism

- High/Low context

- the concept of ‘Face’.

E. References

A. What is culture?

We often talk about ‘ancient cultures’, ‘western culture’, the ‘cultural gap’, a ‘man of culture’…

What do you think the word ‘culture’ means? It may help if you think of your own cultural environment – which elements would you describe as typical?

Maybe you think of architecture, art, music, language, food, dress, literature, habits, values, ways of thinking, rituals and much more. All of these are elements of a certain culture. Sometimes we may talk of national cultures, of local cultures or even the culture of an organisation or social group.

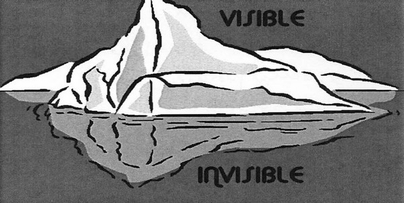

B. The Iceberg model

A useful way to visualize culture is by using the Iceberg model

The iceberg has a visible tip. This is the part of culture we can see in the physical sense. "Visible elements" include things such as music, dress, architecture, language, food, gestures, religious rituals, art and many more.

The part of the iceberg we can’t see – the largest part - includes areas such as religious beliefs, the rules governing relationships, family, motivation, tolerance of change, attitudes to rules and regulations, communication styles, comfort with risk, the difference between public and private spheres, gender differences and more.

It is these invisible elements that are the underlying drivers of those areas of culture which are visible to us. None of the visible elements can ever make real sense without also understanding the drivers behind them.

We all have our own ‘Iceberg’

Perhaps we can reach an even better understanding of the concept of culture if we start by asking ourselves about what we think our own cultural “Iceberg” looks like.

Ask yourself the following questions:

- What does it mean for you when somebody you have an appointment with is not on time – do you think it is disrespectful or not?

- Who would you rather ask if you were desperately in need of some money – your family or the bank?

- If somebody tells you in a straightforward manner that you are mistaken – do you find it helpful or do you feel affronted?

- Do you think that small talk at the beginning of a meeting is important in order to create a good atmosphere or a waste of time?

You will probably notice that it is difficult to answer these questions. It is impossible to be sure what the right answer is in each case. There is no straightforward ‘True’ or ‘False’. What seems right to you will not necessarily be right for somebody else.

How we choose to answer the questions above depend on our own values, attitudes, communication habits, mind sets – there are no ‘right’ answers. These are all elements of our culture which we have internalized since birth. They are passed on from generation to generation and help us find our way through the world. Seen in this way culture can be described as an orientation system (Alexander Thomas, 2005, S.22).

Culture as an orientation system

Culture provides us with an orientation system typical of a specific nation, a specific society, an organisation or a group. The orientation system consists of specific symbols (language, gestures, facial expressions, dress-code, greeting conventions etc.). It is passed on from generation to generation, creating a sense of belonging. Culture defines and influences our perception, our thinking, our values and actions.

We all have internalized our group’s culture and most of the time we are not aware of its function in guiding us through the things we experience in our lives. Our culture-specific orientation system helps us to understand what we see and what we perceive. It provides us with behavioural motivators and opportunities but also sets the conditions and limits of our behaviour (Alexander Thomas). Successful enculturation, - integration into a new culture - requires a process of understanding and, finally, an acceptance of the world in the same way as those who originate from the culture perceive and accept the world.

There are countless other definitions of culture

Culture, understood as an orientation system, is only one of many definitions of culture. Here are some others:

Culture is

- …the part of the environment which is made by humans (Harry Triandis)

- …a collective programming of the mind (Geert Hofstede)

- … the way in which a group of people solve problems (Fons Trompenaars)

Cross-cultural conflict arises when the hidden parts of the ”Iceberg” collide

Have you ever noticed how some cultures unconsciously define respect in different ways? For example some define respect by punctuality and keeping rules, others define respect through harmony and politeness?

Cross-cultural conflicts often arise not because what of what we actually see, but because of something is triggered which deeply disturbs us at an emotional, subconscious level. Do you remember the “Iceberg” model? Cross cultural conflict arises, when two (or more) hidden parts of the iceberg collide.

Each person has their own individual cultural imprint with its own set of values, norm, beliefs and attitudes. These elements help us to understand the world we live in and guide our perception of the world around us. So, depending on our own culture, we will interpret other people’s visible behaviour differently: it may seem more/less strange, acceptable or unacceptable to us. We see the world through our own cultural lens.

C. How to avoid cross-cultural conflict

To avoid cross-cultural conflict we have to learn to see what the world looks like without our own cultural lens. Here are some helpful steps to follow:

Actively observe the situation – when you are disturbed or confused by an incident, take a close look at exactly what has happened or is happening.

Describe the situation - make a mental description of what, specifically, it is that disturbs you in the situation.

Allow multiple interpretations - your cultural background and your cultural orientation system are likely to lend the situation a particular meaning. Remember that in another context and in another culture, what you experience may have a totally different meaning.

Suspend judgement - spend time and effort finding out what the disturbing behaviour really means in that culture. Refer to neutral third parties who are from, or acquainted with, that culture.

Listen actively - make a conscious effort to listen to what you hear. Be aware that your cultural “map” will automatically lead you to filter and interpret what you hear.

Understand perspectives - the more time you can spend understanding the values, beliefs and attitudes of people of other cultures, the higher your chances of long-term co-operation with minimal conflict.

Establish relationship - turn the focus to what you have in common and what you can learn from each other. Remember that all cultures are equally good.

Save face - make it possible for all parties to feel appreciated and respected. Loss of face is a major cause of intercultural conflict. Be aware of your own need not to lose face too.

Develop WIN-WIN solutions - when the ground has been laid for mutual co-operation and understanding, and people are willing to work creatively together on solutions which are good for all parties, a conflict-free future is in sight.

D. Cultural standards - in general and in the medical context

The concept of cultural dimension is a tool that has been developed to help us assess cultures, i.e. to observe, understand and compare cultures. Cultural dimensions provide a basis for reflecxtion concerning behaviour which may seem strange to us.

The dimensions described here are taken from the works of the most well-known developers of cultural dimensions, Geert Hofstede, Fons Trompenaars and Edward T. Hall.

Of course there is the risk of stereotyping when one tries to attribute what are ‘typical’ behaviours. But one has to keep in mind that cultural dimensions are based on what can be observed and what is normal for most members of a certain culture. It is important to remember to approach another culture not by looking at it through one’s own cultural lens but by observing it neutrally and by postponing judgments.

The following dimensions of cultural difference are described below:

1. Power distance

2. Individualism/Collectivism

3. Uncertainty avoidance

4. Masculinity/Femininity

5. Universalism/Particularism

6. High/Low context

7. the concept of ‘Face’.

1) Power Distance

Are you accustomed to hierarchical structures in organisations? Or do you expect to be able to meet your boss in your free time?

This dimension concerns the extent to which an imbalance of power is accepted by a culture. A culture with highly hierarchical structures has a high power distance. Cultures with low power distance have very flat hierarchies.

| LOW Power Distance Index | HIGH Power Distance Index |

| Decentralised decision structures | Centralised decision structures |

| Flat organisational pyramids | Tall organisational pyramids |

| Small proportion of supervisors | Large proportion of supervisors |

| Hierarchy is established for convenience | Hierarchy reflects the existential inequality |

| Consultative leadership | Authority-based leadership |

| Subordinate-superior relations are pragmatic | Subordinate-superior relations are polarised |

| Institutionalised grievance channels | No defence against abuse of superior |

| Privileges and status symbols are frowned upon | Privileges and status symbols are popular and expected |

In a medical context

In patient-doctor relationships the ‘power distance’ dimension is evident in the sort of expectations the patient has towards the doctor and in the way the doctor conveys information to the patient. In some countries, for example Turkey or Afghanistan, patients expect to be told about their illness by the doctor in a clear and authoritative manner. In some countries, such as Germany or Austria for example, doctors tend to ask patients about what they think they need in order to get better. This communication style, originally meant as a way of taking the patient’s wishes seriously and making them feel comfortable, could be interpreted by patients who are not used to it as insecurity and self-consciousness and could lead to a loss of trust and respect.

2) Individualism/Collectivism

Do you see yourself as engaged in a common cause or as an individual standing alone?

Members of collectivist cultures regard themselves as members of a group; they try to align their goals with those of the group and feel an obligation to the common good. Members of individualist cultures regard themselves primarily as autonomous individuals and aim to reach their personal goals independently from the overall interests of their social group.

| Collectivism | Individualism |

| People act in the interest of the group they belong to | People act according to their personal interest |

| Group/family as reference point | Self-determination |

| Tightly-knit social framework | Loosely-knit social framework |

| Group responsibility for tasks | Individual responsibility for tasks |

In a medical context

In a medical context the dimension ‘Individualism/collectivism’ may be evident in the way in which privacy is handled or in the extent to which relatives are involved in decisions concerning the patient’s illness. In more collectivist cultures, such as some in Eastern European, information about a patient’s state of health is given to (and requested from) a wider range of persons than is the case in Northern European cultures. In less collectivist cultures, for example in Russian and Georgia, medical confidentiality is less strict.

In some collectivist cultures, such as some in the Middle East, it is possible for the family to decide on the medical treatment of a family member without consulting the patient or even ignoring their wishes. Here the family decision stands above the will of the individual and may differ from theirs.

3) Uncertainty avoidance

Do you feel comfortable in risky or ambiguous situations?

For people from cultures with high uncertainty avoidance, unclear, unregulated situations create a feeling of disorientation which can even lead to aggression. In such cultures, rules which regulate private and public life tend to attract a high level of respect. For the members of cultures with low uncertainty avoidance, rules to regulate private and public life may be less strictly followed. Chaos and unclear situations are reacted to with relative ease.

| Low Uncertainty Avoidance | High Uncertainty Avoidance UAI |

| Precision and punctuality have to be learned and managed | Precision and punctuality come naturally |

| Power of superiors depends on position | Power of superiors depends on control of uncertainties and relationships |

| Innovators feel independent of rules | Innovators feel constrained by rules |

| Innovation is welcome but not necessarily applied consistently | Innovation is resisted but, if accepted, taken seriously |

| Scepticism towards technological solutions | Strong appeal of technological solutions |

In a medical context

Cultures with a low tolerance for unclear or ambiguous situations have highly defined structures and regulations to prevent unforeseen and therefore stressful events. An emergency situation is in itself a highly unclear and stressful situation – and even more so for people coming from cultures with a low ambiguity tolerance such as Germany or France.

Structured questionnaires for medical histories, clear and simple instructions for colleagues, nurses and patients, rules and regulations given to patients - either in paper format or visible as signposts in an emergency ward, as well as verbal explanations, are all seen as helpful in countries with low ambiguity tolerance in order to avoid unstructured, chaotic situations and reduce stress. It is also important to remember that, in such cultures, waiting can be a cause of stress, particularly when the reason for waiting is not explained or understood.

In low ambiguity tolerance cultures there may be a tendency, during contact time with the patient, for medical staff to rely on written documents or computerized records rather than focusing on direct conversation with the patient. In such cases the patient, as a result, for example, of lack of eye contact, may feel neglected or that they are not being taken seriously which, in turn, could make them lose trust and become less cooperative.

If the doctor comes from a culture with a higher tolerance towards insecurity than the patient, for example Australia or China, the patient may feel that the doctor’s explanations – of the diagnosis or the medication process – are not detailed enough. This may make the patient react with frustration or anger and diminish his/her trust towards the doctor and the medical institution.

4) Masculinity/Femininity (Geert Hofstede)

Do you have many female senior physicians in your country? Do nurses tend to be mostly women?

This dimension expresses the extent to which a culture defines and differentiates between gender roles. In masculine cultures, the social roles of each gender are clearly separated and the male role is characterized by an emphasis on high performance, assertiveness, dominance and material gain. The feminine role is characterized by caring, modesty, subordination, and warm-heartedness. In feminine cultures, roles are not defined by specific characteristics and almost all roles in society can be filled by women as well as by men.

| Femininity | Masculinity |

| Work in order to live | Live in order to work |

| No visible traditional assignment of roles | Visible traditional assignment of roles |

| Meaning of work = relations and working conditions | Meaning of work = security, good pay |

| Stress on equality, solidarity, quality of work life | Stress on equity, competition, performance |

| Successful managers: use intuition, deal with feelings, consensus | Successful managers: firm, aggressive, decisive |

| More women in high positions | Fewer women in high positions |

| Small wage gap between genders | Large wage gap between genders |

| Career ambition optional for both men and women | Career ambition compulsory for men, optional for women |

In a medical context

In cultures with a high masculinity index, like some German speaking and Mediterranean countries, men have more dominant roles in society.

In a medical context, the dimension Masculinity/Femininity may be evident in the distribution of roles: men are ‘naturally’ doctors, researchers etc. – women are ‘naturally’ nurses, laboratory assistants etc. Female patients may be accompanied by men who explain the women’s illnesses without consulting them. Men from countries with a high masculinity index may not like to be treated by women doctors, and may behave in a way which appears arrogant or patronising.

5) Universalism/Particularism (Fons Trompenaars)

Would you help a patient or a colleague in need even if this means disobeying a rule?

This dimension describes how far in a culture rules are universally accepted and obeyed under all circumstances. Universalist cultures are convinced that this is possible, particularist ones focus much more strongly on specific circumstances and reject strict adherence to rules.

| Universalism | Particularism |

| Golden rules (do not lie, do not steal) | Focus on present circumstances, exceptions are possible (I would not steal from a friend) |

| Place greater importance on agreements | Place greater importance on relationships (I must help a friend, no matter what the rules say!) |

In a medical context

In a medical context the dimension ‘Universalism – Particularism’ may be evident in the way that medical staff handle emergency situations. In universalist cultures, all patients are equal and are treated according to the severity of their needs. In particularist cultures, for example some Mediterranean and Arab countries, patients may expect to be given priority because of their relationship to the medical staff - the doctor might be a good friend of the patient’s father or a relative, or the doctor might have some other personal motive for wanting his patient to have preferential treatment. In all these cases, the ‘rules’ undergo renegotiation.

For a patient coming from a particularist culture, adherence to a universalist rule may be incomprehensible or annoying. They may feel they are not being treated with respect and could even become aggressive. For a patient coming from a universalist culture, the particularist system may seem incomprehensible and unfair. The particularist system can cause feelings of insecurity, helplessness and anger.

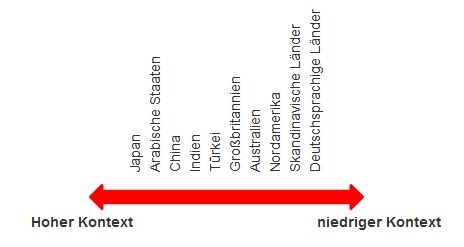

6) High/Low context (Hall)

How direct are you in telling patients about the severity of their illness? How do you choose your words when telling a colleague that their diagnosis is incorrect?

Low context cultures are accustomed to stating explicitly what they mean. The focus will be on the literal meaning of the message. There is no reading between the lines and both non-verbal communication and body language have little importance.

High context cultures communicate with indirect messages. There is much reading between the lines and non-verbal communication is important in decoding meanings correctly.

| High context culture | Low context culture |

| A strong focus on non-verbal communication and contextualised meanings | Little focus on non-verbal communication; overt, explicit messages |

| Reserved, internalised reactions | More focus on verbal communication than on body language |

| Relationship more important than task | Task more important than relationship |

In a medical context

In patient – doctor relationships, the dimension ‘High/Low context’ may be evident in the way patients explain their problem and in the way that medical staff request and give information to patients.

In low-context cultures, such as Scandinavia or German speaking ones, medical staff will deliver information to patients or their relatives in a straightforward manner (“Your heart is in poor condition” “Your liver is enlarged”), without masking the message behind metaphors or other rhetoric. For patients who are not used to this cultural approach, such a direct style of communication may appear unfriendly, offensive or even shocking.

Patients from a high context culture, such as Japan or Arab countries, may appear to medical staff who are more accustomed to direct communication, as reserved or emotionally distant. High-context patients are used to conveying feelings and emotions like insecurity and fear without referring directly to the actual situation (my borders have not been respected > I have been raped). In the eyes of someone from a low context culture, this style of communication may seem unnecessarily lengthy and evasive. Equally, if a doctor uses an expression such as ‘Your borders have not been respected’ this may be almost incomprehensible to a patient who is accustomed to a much more direct way of speaking, using words such as “rape” and “violation”.

7) The concept of ‘Face‘

The concept of ‘Face‘, although not defined as a cultural dimension, is nevertheless a widespread behavioral phenomenon.

Face is a term which is used particularly in Asian cultures, especially China. The notion of ‘face’ also exists in Western societies where it may be called ‘honour’, ‘prestige’, or ‘standing’. In both Asian and Western cultures, ‘saving face’ can be particularly important and transgression of social norms and behaviour can lead to loss of face. In Asian cultures particularly, people tend to strive not only to avoid losing their own face but not to cause others to lose theirs. They also cooperate to help others to gain face.

In a medical context

Some patients, especially those from Asian countries, may not want to show that they have not understood a question or that they disagree with the medical staff. This would lead not only to their loss of face but also that of the other person. In such instances, it can be difficult to get a clear answer from the patient. It may be better for medical staff to try to put into words what the patient may be feeling (‘I imagine that you might find this information shocking’). This might make it easier to draw out the patient’s feelings or opinions.

E. References

Matthias Bastigkeit, Können Sie mich verstehen? Sicher kommunizieren im Rettungsdienst. Wien 2005.

Silke A. Becker, Eva Wunderer, Jürgen Schulz-Gambard, Muslimische Patienten. Ein Leitfaden zur interkulturellen Verständigung im Krankenhaus und Praxis. 3. Ed. Wien/New York 2006.

Geert Hofstede, Culture and Organization – Software of the Mind, London 1991.

Ilhan Ilkilic, Begegnung mit muslimischen Patienten. Eine Handreichung für die Gesundheitsberufe. Reihe Zentrum für Medizinische Ethik. Medizinethische Materailien, Heft 160 Burkhard May, Hans Martin Sass, Michael Zenz (eds.), 6. Ed., Bochum 2005.

Malika Laabdallaoui, Ibrahim Rüschoff, Umgang mit muslimischen Patienten, Bonn 2010.

Michael Peintinger (ed.), Interkulturell kompetent. Ein Leitfaden für Ärztinnen und Ärzte, Wien 2011.

Alexander Thomas, „Kultur und Kulturstandards“, in: Alexanter Thomas/Eva-Ulrike Kinast/Sylvia Schroll-Machl (eds.), Handbuch Interkulturelle Kommunikation und Kooperation, vol. 1, 2. Ed., 2005.

Harry C. Triandis, „Intercultural Education and Training“, in: Peter Funke (ed.), Understanding the US – Across Culture Prospective, Tübingen 1989.

Fons Trompenaars, Riding the waves of culture, 2. Ed., London 2010.

Charlotte Uzarewicz/Gudrum Piechotta (eds.), Trankulturelle Pflege, Reihe Sonderband zu Curare, 10, Berlin 1997.